Web Stories

Latest Blogs

Rare Disease Day 2026: Raising Awareness, Challenges, And The Importance Of Early Diagnosis

What Is Rare Disease Day? Rare Disease Day is a global awareness campaign observed every year on the last day of February (28 February, or 29 February in leap years). It was first held on 29 February 2008 and is now marked in more than 100 countries. The day aims to raise awareness for over 300 million people worldwide living with rare diseases and to promote equitable access to diagnosis, treatment, research, and social care. In India, the term generally refers to conditions that affect a small proportion of the population and often require specialised diagnosis and care.. There are over 6,000 identified rare diseases, and nearly 72 percent are genetic. The campaign brings together patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers. Symbolised by zebra stripes, Rare Disease Day reminds you that while each condition is uncommon, collectively they affect millions and require timely diagnosis and compassionate care. Rare Disease Day 2026 Theme The Rare Disease Day 2026 theme is yet to be officially confirmed. Current campaign materials indicate “More Than You Can Imagine,” highlighting the hidden and far-reaching impact of rare diseases worldwide. Theme: The official 2026 theme is expected to focus on “More Than You Can Imagine,” highlighting the hidden and far-reaching impact of rare diseases worldwide. (Theme subject to official confirmation.) Recognises the physical, emotional, and financial challenges faced by over 300 million people Emphasises that 6,000 to 10,000 rare diseases collectively affect millions of families Calls for equitable access to timely diagnosis, treatment, and care Encourages reducing diagnostic delays and improving specialised services Promotes global solidarity through initiatives such as “Light Up For Rare” Invites you to raise awareness using the #RareDiseaseDay campaign The theme reinforces the need for compassion, equity, and collective action to improve lives. Global Participation In Rare Disease Day Rare Disease Day unites people worldwide to raise awareness and advocate for better care. Observed in over 100 countries Awareness events, webinars, and community programmes Policy advocacy for equitable diagnosis and treatment Social media campaigns sharing stories and rare disease day quotes “Light Up For Rare” solidarity initiatives Together, global participation helps amplify patient voices and promote earlier diagnosis and fair access to care. How To Observe Rare Disease Day? Individuals can observe Rare Disease Day by taking simple yet meaningful steps to raise awareness and support those affected. Mark 28 February 2026 and participate in awareness activities. Wear zebra stripes to show solidarity. Share posts, rare disease day quotes, and stories using #RareDiseaseDay. Join or organise walks, webinars, or community events. Take part in the “Light Up For Rare” initiative. Support early diagnosis and advocate for better access to care. Your involvement can help promote awareness, reduce stigma, and encourage timely diagnosis. Quotes For Rare Disease Day 2026 You can use meaningful messages and rare disease day quotes to spread awareness and show solidarity. “More Than You Can Imagine.” “Rare, but not alone.” “Alone we are rare, together we are strong.” “Early diagnosis changes lives.” “Equity in healthcare for every patient.” “Every patient matters.” “300 million people worldwide are living with a rare disease. Together, their voices are powerful.” “Rare diseases are not invisible. Every story deserves to be heard.” Sharing these messages can help raise visibility, reduce stigma, and promote equity in diagnosis and care. The Importance Of Rare Disease Awareness Rare disease awareness plays a vital role in improving early and accurate diagnosis, advancing research, and strengthening patient support. Between 3.5% and 5.9% of the global population (approximately 1 in 17 to 1 in 28 people) may live with a rare disease, yet many face years of misdiagnosis due to overlapping symptoms and limited clinical familiarity. Greater awareness helps reduce diagnostic delays, enables timely intervention to prevent complications, and improves access to genetic counselling and specialised care. It also drives research funding and policy changes, especially since only a small percentage of rare diseases have approved treatments. Most importantly, awareness reduces stigma and isolation, ensuring that patients and families feel seen, supported, and empowered to seek the right diagnostic evaluation. Rare Disease Day 2026 Events And Activities Rare Disease Day 2026, observed on 28 February, will feature global and local initiatives aimed at promoting awareness, equity, and early diagnosis. Global Awareness Campaigns: Community walks, marathons, virtual runs, and public gatherings supporting rare disease advocacy Educational Events: Webinars, expert talks, scientific conferences, and patient-focused discussions Policy And Advocacy Meetings: Roundtables encouraging improved access to diagnosis, treatment, and research funding Global Chain Of Lights: Landmarks and homes illuminated in campaign colours to show solidarity School And College Programmes: Awareness sessions to educate students and young adults Patient Story Initiatives: Sharing real-life experiences to reduce stigma and strengthen community support Virtual Participation Options: Online events enabling worldwide involvement These activities aim to build awareness, improve access to care, and foster a more inclusive healthcare environment for people living with rare diseases. can you combine these options and create a new for the faq - List Of Rare Diseases Rare diseases affect a small percentage of the population. In India, they are generally considered conditions that impact a very small proportion of people and often require specialised care. Globally 6,000 to 10,000 rare diseases have been identified, and nearly 90 to 95 percent lack approved targeted treatments, making early diagnosis essential. They are broadly classified into: Metabolic Disorders: Pompe disease, Gaucher disease, Fabry disease, Phenylketonuria Neurological And Genetic Disorders: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Spinal muscular atrophy, Huntington’s disease Autoimmune And Blood Disorders: Sickle cell disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome Congenital And Structural Conditions: Cystic fibrosis, Osteogenesis imperfecta, Turner syndrome Immune Deficiency Disorders: X linked agammaglobulinemia Because symptoms often resemble common illnesses, timely genetic testing and specialised diagnostic evaluation are crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. Local Initiatives For Rare Disease Day In India, local initiatives for Rare Disease Day focus on raising awareness, promoting early diagnosis, and improving access to specialised care. Activities include “Light Up For Rare” landmark illuminations, community walks and awareness drives, educational programmes in schools and colleges, and social media campaigns such as “Show Your Stripes.” Healthcare institutions may organise webinars, screening camps, and training programmes to help doctors recognise early symptoms. Advocacy efforts also support expanded newborn screening, improved access to genetic testing, multidisciplinary care, and stronger health policies. These initiatives aim to reduce diagnostic delays and ensure timely, appropriate management for people living with rare diseases. Rare Disease Day 2026: Key Statistics Rare Disease Day 2026 highlights the scale, challenges, and urgent need for equitable care for people living with rare conditions. Global Burden Over 300million people worldwide are affected 3.5 to 5.9 percent of the global population lives with a rare disease Between 6,000 and 10,000 rare diseases have been identified Nature Of Rare Diseases Around 72 to 80 percent are genetic in origin Nearly 70 percent of genetic rare diseases begin in childhood Almost one in five cancers is classified as rare Diagnostic And Treatment Gaps Many patients face five or more years before receiving an accurate diagnosis Around 90 to 95 percent of rare diseases lack approved targeted treatments 2026 Focus Observed on 28 February 2026 Theme: “More Than You Can Imagine” Marked in over 100 countries to promote equity in diagnosis, treatment, and research These figures reinforce the importance of awareness, early detection, and improved access to specialised care. FAQs How Can I Participate In Rare Disease Day 2026? You can participate by sharing awareness messages using #RareDiseaseDay, wearing zebra stripes, joining the “Light Up For Rare” initiative, attending events, advocating for early diagnosis and better care, and supporting patient organisations. Which Diseases Are Considered Rare? Rare diseases affect a small percentage of the population, in India, rare diseases generally affect a very small percentage of the population and often require specialised care. Most are genetic, chronic, and progressive, including metabolic disorders, neuromuscular diseases, immune deficiencies, autoimmune conditions, rare cancers, and congenital syndromes. Early diagnosis is essential for appropriate care. Where Are The Rare Disease Day Events Taking Place? Rare Disease Day events are held worldwide on or around 28 February in hospitals, research centres, schools, universities, and community spaces. Activities include webinars, awareness programmes, advocacy meetings, and landmark illuminations as part of the “Light Up For Rare” initiative. How Does Rare Disease Day Help People With Rare Diseases? Rare Disease Day raises awareness, promotes research funding, and advocates for equitable access to diagnosis and treatment. It amplifies patient voices, reduces stigma, and brings together patients, clinicians, and policymakers to improve care and quality of life. What Are Some Examples Of Rare Diseases? Rare diseases are often genetic and chronic, with over 6,000 to 10,000 identified worldwide. Examples Include: Neuromuscular Disorders: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Spinal muscular atrophy Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Gaucher disease, Fabry disease, Pompe disease Genetic Conditions: Cystic fibrosis, Huntington’s disease, Phenylketonuria Autoimmune And Neurological Disorders: Guillain-Barré syndrome, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Rare Cancers: Mesothelioma, Paediatric medulloblastoma Early diagnosis and specialised care are important due to limited treatment options. Why Is Awareness About Rare Diseases Important? Awareness helps reduce diagnostic delays, improve access to specialised care, drive research funding, strengthen health policies, and reduce stigma, ensuring better support and outcomes for people living with rare diseases. References Nguengang Wakap S, Lambert DM, Olry A, Rodwell C, Gueydan C, Lanneau V, et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28(2):165-173. PMID:31666360. Ferreira CR. The burden of rare diseases. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179(6):885-892. PMID:30825377. Boycott KM, Vanstone MR, Bulman DE, MacKenzie AE. Rare-disease genetics in the era of next-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(10):681-691. PMID:23999272. Zurynski Y, Frith K, Leonard H, Elliott E. Rare childhood diseases: How should we respond? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(12):1071-1074. PMID:18838475. Taruscio D, Vittozzi L, Stefanov R. National plans and strategies on rare diseases in Europe. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:475-491. PMID:20824458.

Brain Function Explained: Roles, Regions, and How It Works

Your brain is the control centre of your body. It keeps you alive by managing automatic tasks like breathing, heartbeat, and temperature regulation. At the same time, it drives the abilities that shape your everyday life, like thinking, learning, memory, emotions, language, decision-making, and movement. In simple terms, brain function is the combined work of many brain regions that receive information from your senses and body, process it, and send commands through the nervous system. This guide explains brain anatomy and function in a clear, patient-friendly way. You will learn what the brain controls, what the major brain parts do, how brain signalling works, what can affect brain function day to day, warning signs that need urgent care, and how doctors evaluate brain-related symptoms. Medical note: This content is for general awareness and does not replace medical advice. If you have sudden or severe symptoms, seek urgent medical care. What Is Brain Function? Brain function refers to how the brain controls and coordinates vital body processes and mental abilities by receiving signals, interpreting them, and sending instructions. The brain and spinal cord together form the central nervous system (CNS), which communicates with the rest of the body through nerves. In one line: Brain function is how your brain keeps your body running and enables thinking, feeling, sensing, and moving. What Does the Brain Control? Brain function covers a wide range of responsibilities. It helps to think of them in four groups. Vital Automatic Functions These are processes you do not consciously control, such as: Breathing and breathing rhythm Heart rate and blood pressure regulation Body temperature control Sleep and wake cycles Swallowing and protective reflexes like coughing Cognition and Emotion These include: Attention and concentration Learning and memory Language and communication Planning, judgement, and decision-making Emotions, mood, and stress response Creativity and problem-solving Movement and Coordination Movement takes more than muscle strength. It also needs timing and precision: Voluntary movement like walking, writing, and speaking Posture and balance Fine motor control like buttoning a shirt or typing Sensory Processing The brain interprets signals from: Vision and hearing Touch, pain, and temperature Taste and smell Body awareness, meaning your sense of position and movement Major Parts of the Brain and Their Roles Most basic brain diagrams describe three major parts: the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem. Each has a distinct job, and they work together constantly. Cerebrum (Largest Part) The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain and handles many higher functions. It plays a key role in: Thinking, learning, memory, and attention Emotions and behaviour Interpreting sensory information Starting voluntary movement The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, left and right. Some functions may be more dominant on one side in many people, such as language. Still, most daily tasks involve both hemispheres working together. The hemispheres share information through bundles of nerve fibres that help messages move across the brain efficiently. Cerebellum (Coordination and Balance) The cerebellum sits toward the back of the brain. It is best known for: Coordinating movement so it is smooth and accurate Maintaining balance and posture Supporting motor learning, meaning skills improve with practice Brainstem (Vital Life Functions and Relay) The brainstem connects the brain to the spinal cord. It supports essential functions, including: Breathing Heart rate and blood pressure regulation Wakefulness and basic alertness Swallowing and other reflexes It also acts as a relay pathway, carrying messages between the brain and the rest of the body. Brain Lobes and What Each One Does The cerebrum’s outer layer, called the cerebral cortex, is commonly described in four lobes. Each lobe is specialised, which is why “brain lobe functions” is such a useful way to understand the brain. Frontal Lobe The frontal lobe is associated with: Planning, reasoning, and decision-making Personality and behaviour Voluntary movement Attention and self-control Speech production in many people Parietal Lobe The parietal lobe helps with: Processing touch, pain, and temperature Body awareness, like knowing where your limbs are without looking Spatial perception, meaning understanding where you are relative to objects Temporal Lobe The temporal lobe supports: Hearing and sound processing Memory and recall Emotion-related processing Language comprehension in many people Occipital Lobe The occipital lobe is primarily responsible for: Visual processing and interpretation Quick Reference Table (Brain Parts and Functions) Brain Lobe Main Roles Examples of What May Be Affected if the Lobe Is Not Working Well Frontal Planning, behaviour, movement, speech production Poor planning, personality changes, movement difficulty Parietal Touch processing, body awareness, spatial skills Trouble sensing touch or position, clumsiness in spatial tasks Temporal Hearing, memory, language comprehension Memory issues, difficulty understanding speech Occipital Vision Trouble interpreting visual information Note: Symptoms can overlap and can also occur due to many non-brain causes. Always consult a clinician for diagnosis. Inside the Brain: Key Structures You May Hear About Beyond the lobes, deeper brain structures help regulate sensation, hormones, sleep, emotion, and memory. Thalamus The thalamus acts like a relay station for sensory information, sending signals onward for processing. Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland The hypothalamus helps regulate core body functions such as: Hunger and thirst Temperature regulation Sleep patterns Stress response It works closely with the pituitary gland, which influences many hormone-driven functions throughout the body. Hippocampus The hippocampus is strongly linked to learning and memory formation, especially forming new memories. Amygdala The amygdala is involved in emotion processing, especially emotional learning and threat-related responses. Limbic System: Emotions and Memory The limbic system is a network of brain structures that work together to support emotion, motivation, learning, and memory. It includes areas such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and parts that interact closely with the hypothalamus. In everyday terms, the limbic system helps you: Attach emotions to experiences, which influences what you remember Learn from rewards and threats, shaping habits and decision-making Regulate stress responses that affect sleep, appetite, and focus Because the limbic system is closely linked to stress hormones and sleep regulation, ongoing stress and poor sleep can affect mood, memory, and mental clarity in noticeable ways. Gray Matter vs White Matter Gray matter is heavily involved in processing and interpretation. White matter helps transmit signals between brain regions. Think of it as the communication network linking different processing areas. Both are essential for healthy brain function. How the Brain Works: Neurons, Signals, and Networks Neurons and Supporting Cells The brain contains billions of neurons, which are nerve cells responsible for sending and receiving signals. It also contains supporting cells that help maintain a healthy environment, support connections, and protect nerve tissues. Electrical Signals and Chemical Messengers Brain communication happens in two steps: Electrical signals travel through neurons. Neurotransmitters, which are chemical messengers, carry messages across tiny gaps between neurons called synapses. This fast signalling is what allows you to react quickly, learn new things, remember, control movement, and regulate emotions. Networks, Not Single Centres Many abilities are not controlled by one single spot in the brain. Instead, brain function relies on networks of regions working together. For example: Speaking involves language planning, motor control, hearing feedback, memory, and attention. Balance involves sensory input from the eyes and inner ear, cerebellar coordination, and muscle feedback. Left Brain vs Right Brain It is common to hear “left brain is logical” and “right brain is creative.” There can be some specialisation, but most real skills use both sides working together. Brain Development Across Life Early Development to Teens From infancy through adolescence, the brain rapidly develops connections and refines them through learning and experience. Maturation Into the Mid to Late 20s Brain development continues beyond the teenage years. The prefrontal cortex, important for planning, prioritising, decision-making, and impulse control, continues to mature into the mid to late 20s. Ageing and Brain Function With ageing, some people notice slower recall or processing speed. Still, sudden confusion or rapid loss of daily functioning is not typical and should be evaluated. What Can Affect Brain Function Day to Day? Many everyday factors influence how you feel mentally, especially your energy, focus, mood, and clarity. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Sleep supports attention, memory, mood regulation, and reaction time. Poor sleep can lead to brain fog, irritability, and low mental stamina. Nutrition and Key Nutrients The brain needs steady energy and essential nutrients. In some people, deficiencies may contribute to fatigue, poor concentration, mood changes, or nerve-related symptoms. Nutrients often discussed in brain health include: Vitamin B12 Iron Vitamin D Omega-3 fats through diet Supplements should be taken only when needed and ideally under medical guidance. Stress and Mental Health Stress can affect sleep, attention, memory retrieval, and emotional regulation. Persistent anxiety or low mood can feel like poor concentration and mental fatigue. If symptoms are ongoing, professional support can help. Physical Activity and Blood Flow Regular movement supports cardiovascular health and can improve sleep quality, mood, and energy, which in turn affects daily brain function. Metabolic Health Metabolic issues can contribute to fatigue and reduced mental clarity in some people. Examples include blood sugar fluctuations and thyroid hormone imbalance. If symptoms persist, discuss a clinician-guided evaluation. Alcohol, Substances, and Medications Alcohol and certain substances can affect memory, reaction time, sleep, and coordination. Some prescription medications can also cause drowsiness, dizziness, or cognitive side effects. Do not stop or change prescribed medication without medical advice. Common Conditions Affecting Brain Function Many conditions can affect brain function directly or indirectly. Some develop gradually, while others appear suddenly and need urgent care. Below are examples clinicians commonly consider when symptoms involve memory, balance, speech, strength, sensations, mood, or alertness. Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA) A stroke occurs when blood flow to part of the brain is interrupted or when bleeding occurs in the brain. A TIA is sometimes called a mini-stroke and can cause temporary symptoms that resolve, but it still needs urgent medical evaluation because it can signal a higher stroke risk. Common warning signs include sudden facial drooping, weakness on one side, speech difficulty, and sudden vision changes. Seizures and Epilepsy Seizures occur due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. They can cause convulsions, staring spells, confusion, unusual sensations, or brief loss of awareness. Epilepsy is typically diagnosed when a person has a tendency for recurrent unprovoked seizures. Migraine and Other Headache Disorders Migraine is more than a headache. It can involve nausea, sensitivity to light or sound, and in some people, aura symptoms like visual changes or tingling. Severe or unusual headaches should be evaluated, especially if sudden or associated with weakness, fever, confusion, or neck stiffness. Concussion and Head Injury Even a mild head injury can affect concentration, memory, reaction time, sleep, and mood for days or weeks. Red flags after a head injury include worsening headache, repeated vomiting, confusion, seizures, weakness, or increasing drowsiness. Neurodegenerative Conditions Conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease can affect memory, movement, behaviour, or daily functioning over time. Early evaluation matters because some contributing factors are treatable, and planning and support can improve quality of life. Infections and Inflammation Affecting the Brain Infections like meningitis and encephalitis can affect brain function and may cause fever, severe headache, confusion, seizures, neck stiffness, or sensitivity to light. These symptoms require urgent medical assessment. Metabolic and Hormonal Causes Brain fog, fatigue, dizziness, and memory lapses can sometimes be linked to non-brain causes such as thyroid imbalance, vitamin B12 deficiency, anaemia, electrolyte imbalance, liver or kidney dysfunction, or blood sugar fluctuations. This is why clinicians often include targeted blood tests during evaluation. Note: Symptoms alone cannot confirm the cause. A clinician’s assessment, and tests when appropriate, help clarify what is going on. Symptoms That May Suggest Brain Function Is Affected Common, Non-Specific Symptoms These symptoms can have many causes, including lifestyle factors: Brain fog or poor concentration Headaches Dizziness Memory lapses Sleep disturbances Mood changes Fatigue and low mental stamina If symptoms persist, worsen, or interfere with daily life, consult a clinician. Red Flag Symptoms That Need Urgent Medical Care Seek emergency help immediately if you notice: Sudden weakness or numbness, especially on one side of the body Facial drooping Difficulty speaking or understanding speech Sudden severe headache Seizure Fainting or loss of consciousness Sudden vision loss or major vision changes Sudden trouble walking, severe dizziness, or loss of balance or coordination If you are in India, you can call 112 for emergency assistance. How Doctors Evaluate Brain-Related Symptoms History and Neurological Exam Clinicians typically start with questions like: When did the symptoms begin, sudden or gradual? Are symptoms constant or episodic? Any triggers such as sleep loss, infection, stress, or medication changes? Any associated symptoms such as fever, weight changes, weakness, or speech issues? A neurological exam may assess strength, sensation, reflexes, coordination, balance, speech, and memory. Imaging and Specialised Tests (When Needed) Depending on symptoms, a doctor may recommend tests such as CT or MRI scans, and sometimes EEG in specific situations. Lab Tests That Can Support Evaluation Blood tests can help identify factors that may contribute to symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, or weakness. A clinician may recommend: Complete Blood Count (CBC) to look for patterns that may suggest anaemia or infection Thyroid Profile (TSH, T3, T4) to assess thyroid balance Vitamin B12 to check for deficiency linked to nerve-related symptoms Vitamin D often checked in persistent fatigue and general health evaluations Blood Glucose or HbA1c to assess blood sugar control Lipid Profile to support long-term cardiovascular risk assessment Electrolytes (Sodium, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium) since imbalances can contribute to weakness, fatigue, or confusion CRP in appropriate clinical contexts to assess inflammation If your clinician advises testing, you can book these blood tests with Metropolis Healthcare and review the results with your doctor for interpretation and next steps. Brain Health Basics: Simple Habits That Support Brain Function Keep a Consistent Sleep Routine Aim for regular sleep and wake timings. If sleep is poor, reduce caffeine late in the day and limit screen time before bed. Eat a Balanced, Varied Diet Include proteins, whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats. If you follow a restrictive diet or suspect deficiencies, speak with a clinician about appropriate testing. Stay Physically Active Even moderate activity supports mood, energy, and sleep quality. Manage Stress Proactively Breathing exercises, journaling, physical activity, social connection, and professional support can all help. Protect Your Head Wear helmets for two-wheelers and sports, wear seatbelts, and take head injuries seriously. Keep Chronic Conditions Under Control Work with your clinician to manage blood pressure, diabetes, thyroid disorders, and other long-term conditions that affect overall wellbeing. Final Takeaway Brain function is not one single action. It is a coordinated system involving specialised regions that work together every second. Understanding the brain’s parts and functions helps you recognise what is normal, what may be influenced by lifestyle factors, and when symptoms need medical attention. If you are experiencing persistent fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, or memory changes, a clinician-guided evaluation, including relevant blood tests, can help identify contributing factors and guide next steps. FAQs How much does the human brain weigh? In adults, the brain typically weighs about 1.3 to 1.4 kilograms, roughly 3 pounds, with normal variation across individuals. Brain weight does not determine intelligence. Brain function depends more on neural connections, network efficiency, health, and life experience. What Is Brain Function in Simple Words? Brain function is how your brain keeps your body running and enables thinking, memory, emotions, senses, and movement. What Are the Three Main Parts of the Brain and Their Functions? The cerebrum supports thinking and voluntary actions, the cerebellum coordinates balance and movement, and the brainstem controls vital automatic functions like breathing and heart rate. Which Brain Lobe Controls Vision, Memory, and Speech? Vision is mainly processed in the occipital lobe. Memory involves the temporal lobe and deeper structures like the hippocampus. Speech typically involves frontal and temporal regions for production and comprehension. How Do Neurons Communicate? Neurons communicate through electrical signals within the neuron and neurotransmitters across synapses between neurons. What Is the Difference Between Gray Matter and White Matter? Gray matter is more involved in processing information, while white matter helps transmit signals between brain regions. Is the Left Brain Logical and the Right Brain Creative? There can be some specialisation, but most tasks use both sides working together. At What Age Does the Brain Fully Develop? Many parts of the brain continue maturing into the mid to late 20s, especially areas involved in planning and self-control. What Causes Brain Fog? Brain fog can be linked to poor sleep, stress, dehydration, medication effects, and medical factors like vitamin deficiencies or thyroid imbalance. If it persists, consult a clinician. When Should I Worry About Memory Problems? If memory changes are sudden, worsening, or affecting daily life, or if they occur with red flag symptoms, seek medical evaluation. Which Blood Tests Might a Doctor Suggest for Fatigue or Brain Fog? Common tests include CBC, thyroid profile, vitamin B12, vitamin D, glucose or HbA1c, electrolytes, and sometimes CRP depending on symptoms.

Brain Fog: Meaning, Causes, Symptoms and Fixes

Have you ever felt mentally cloudy, like your brain is moving slower than usual, or like you are not as sharp as you normally are? That experience is often described as brain fog. It can be frustrating because it affects the basics: focusing at work, following conversations, remembering small details, and staying mentally present. Brain fog is not a medical diagnosis. It is a cluster of symptoms that can happen for many reasons, including poor sleep, stress, dehydration, hormonal shifts, nutrition gaps, illness recovery, or medication side effects. In this article, you will learn what brain fog means, what it feels like, the most common causes, practical ways to improve it, when to see a doctor, and what tests may help identify contributing factors. Medical note: This content is for general awareness and does not replace medical advice. If you have severe, sudden, or worrying symptoms, seek urgent medical care. What Is Brain Fog? Brain fog is a term people use to describe mental cloudiness with reduced clarity, focus, and memory, often paired with mental tiredness. It is usually a signal that something is affecting your brain’s day-to-day performance, such as poor sleep, stress, nutrition issues, hormonal changes, illness recovery, or certain medications. Brain fog in one sentence: Brain fog is the feeling of mental cloudiness that makes thinking, focusing, and remembering harder than usual. What Brain Fog Feels Like Brain fog often feels like your mind is “buffering,” like a slow phone that takes longer to respond. You know you should be able to think clearly, but everything feels delayed, fuzzy, or harder than usual. Common experiences include: Losing your train of thought mid-sentence Reading the same paragraph repeatedly without absorbing it Forgetting why you entered a room Struggling to find the right word during a conversation Feeling mentally tired even after small tasks, like replying to messages Some days it is mild and manageable. Other days it can make routine work feel surprisingly difficult. Symptoms of Brain Fog Common Symptoms Brain fog can look different from person to person, but these are some of the most common signs: Difficulty focusing or paying attention Forgetfulness and short-term memory slips (names, dates, small tasks) Slow thinking and slower reaction time Word-finding difficulty (you know what you want to say, but the word does not come) Mental fatigue, feeling “spaced out” or not fully present Trouble multitasking or learning new information A quick self-check: if you notice several of these symptoms regularly for days or weeks, it is worth looking for patterns and triggers rather than brushing it off as “just being busy.” Causes of Brain Fog Brain fog is often caused by more than one factor. That is why it helps to start with the most common triggers first and work step by step. Lifestyle Causes These are some of the biggest and most fixable contributors: Poor sleep or an irregular sleep schedule Chronic stress and burnout Dehydration, especially if you rely heavily on caffeine Skipping meals or eating mostly sugary and refined foods that cause energy crashes Too much alcohol, which can affect sleep quality and attention Overload, meaning too much screen time, too many tasks, and not enough breaks If brain fog started during a busy period, lifestyle factors are often a major piece of the puzzle. Hormonal Changes Hormones influence sleep, mood, and mental performance. Brain fog may occur with: Menstrual cycle changes Pregnancy and the postpartum period Perimenopause and menopause If symptoms seem to follow a cycle or life phase, tracking timing can help you and your clinician understand what is going on. Mental Health and Emotional Load Your brain struggles to focus when it is under emotional pressure. Anxiety and low mood can reduce attention, motivation, and working memory High stress can worsen sleep and concentration This does not mean symptoms are imagined. It means brain fog can be part of how your mind and body respond to prolonged strain. Medical Contributors That Are Often Treatable Brain fog does not always mean something serious. Often there are common and treatable contributors, such as: Thyroid imbalance Low iron or anaemia Vitamin B12 deficiency Blood sugar issues, including diabetes or low blood sugar episodes Vitamin D deficiency, which is commonly checked in fatigue workups Only a clinician can confirm whether these apply to you, but it helps to know these are common possibilities. Infections and Recovery Periods Brain fog can occur during recovery, especially after illness: Brain fog after a viral illness is common and often temporary Long COVID is a recognised trigger for ongoing concentration and fatigue issues in some people If your brain fog began after an infection, pacing yourself and giving your body time to recover can matter as much as rest. Chronic Conditions Sometimes Linked With Brain Fog Brain fog can be reported alongside some longer-term conditions, including: Autoimmune conditions Chronic fatigue-related syndromes Neurological conditions (in a general sense) This does not mean brain fog automatically points to these conditions. It simply means brain fog can occur in many contexts. Medications and Substances Some medicines can cause drowsiness, slowed thinking, or attention problems. Alcohol and other substances can also worsen focus and sleep quality. Safety note: do not stop medicines without medical advice. If symptoms began after starting a new medication, discuss it with your clinician. A helpful way to think about it: brain fog often comes from a combination, like stress plus poor sleep plus low iron, rather than one single cause. Brain Fog, Dementia, and Delirium: Key Differences It is common to worry that brain fog might be dementia. Most of the time, it is not, but it is still important to understand how they differ. Brain fog is usually fluctuating and often linked to triggers like sleep loss, stress, illness recovery, dehydration, or lifestyle patterns. Dementia is generally progressive over time and increasingly affects daily functioning. Delirium is sudden confusion and is a medical emergency. It may involve disorientation, severe confusion, or changes in alertness. If your symptoms are worsening quickly, affecting safety, or paired with red flag symptoms, seek urgent medical care. How to Clear Brain Fog The most effective approach is to reduce what is draining your brain and build habits that support steady energy, sleep quality, and recovery. You do not need to do everything. Start with a few changes you can maintain. Quick Improvements in the Next 24 to 72 Hours These steps can help quickly, especially when lifestyle factors play a role: Hydrate consistently and eat regular meals Reduce late caffeine and alcohol Take a short walk or do light exercise Take 10-minute breaks with no screens between mentally demanding tasks Use a simple to-do list and do one task at a time Even small changes can improve mental clarity more than you expect. Resetting Sleep for Better Mental Clarity Sleep is one of the biggest drivers of focus and memory. Keep consistent sleep and wake times, even on weekends Get morning sunlight exposure to support your body clock Set a screen cut-off time before bed Keep the bedroom dark, quiet, and cool If you wake up tired often, snore heavily, or feel unusually sleepy in the day, speak with a clinician. Sleep problems are common and treatable. Food and Nutrition Habits That Support Focus You do not need a strict diet. You need steady fuel. Aim for protein with breakfast to reduce energy crashes Choose balanced meals to avoid glucose spikes and crashes Include iron and B12 rich foods, without expecting overnight results If you are vegetarian or vegan, be mindful of B12 intake and consider discussing testing if symptoms persist If you suspect certain foods make symptoms worse, a simple food and symptom diary can help identify patterns Stress Management That Fits Real Life Stress is part of life, but you can reduce its mental cost. Try a 5-minute breathing routine once or twice a day Use movement breaks to reset attention Set boundaries around workload where possible Build recovery time into the day, not just the weekend If anxiety or low mood is persistent, speaking with a mental health professional can help. Better mental health often improves sleep and focus. Focus Strategies for Busy Days When you must perform, reduce friction. Single-task whenever possible Use timed focus blocks (for example 25 minutes focus, 5 minutes break) Reduce distractions and work in a quieter space Write things down, use reminders, and keep simple routines Brain fog often worsens when you try to multitask. One task at a time usually works better. A Simple 2-Week Plan If you want a clear plan, try this: Week 1 Improve sleep timing as much as possible Increase hydration Add a daily walk, even if it is 15 to 20 minutes Week 2 Keep sleep steady Shift meals toward balanced plates and reduce high sugar snacks Add a short daily stress routine Cut back alcohol Track symptoms briefly in a note app: what improves, what worsens, and when you feel best. This can reveal triggers you did not notice before. When to See a Doctor See a Clinician If Brain fog lasts more than 2 to 3 weeks It is getting worse It affects work, driving, or daily tasks You have new symptoms like significant mood changes, weakness, or persistent headaches Seek Urgent Medical Care If You Notice Red Flags Sudden weakness or numbness, especially one-sided Facial drooping Trouble speaking or understanding speech Severe sudden headache Seizure Fainting or severe confusion Sudden vision loss Severe imbalance If you are in India, you can call 112 for emergency assistance. How Brain Fog Is Evaluated History and Basic Examination Clinicians usually start with questions about: Sleep, stress, diet, hydration Recent illness or infection recovery Medicines and supplements Mood, workload, burnout, and life changes Other symptoms like headaches, dizziness, weakness, or appetite changes A basic neurological and general assessment may check coordination, reflexes, attention, and overall health. Lab Tests That May Help Identify Contributing Factors Your doctor may recommend tests to rule out common contributors, such as: Complete Blood Count (CBC) Iron studies (if clinically indicated) Thyroid Profile (TSH, T3, T4) Vitamin B12 Vitamin D Blood glucose or HbA1c Electrolytes (Sodium, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium) CRP (when inflammation is suspected) If your clinician advises tests, you can book them with Metropolis and review the results with your doctor for interpretation and next steps. Imaging and Diagnostic Tests to Identify Brain Fog There is no single scan or machine test that “detects brain fog.” Instead, imaging and other diagnostic tests are used selectively when a clinician wants to rule out specific neurological causes or investigate concerning symptoms. A doctor may consider additional testing if brain fog is persistent, worsening, affects safety, or is accompanied by symptoms like severe headaches, fainting, seizures, weakness, numbness, speech changes, vision changes, or changes in alertness. Common tests that may be recommended in certain situations include: CT or MRI brain: These scans may be used when there are red flags, a history of head injury, new neurological signs, or concern for causes such as stroke, bleeding, inflammation, or structural changes. EEG: This test measures brain electrical activity and may be advised if seizures are suspected or if there are episodes of unexplained confusion or altered awareness. Sleep testing: If symptoms include loud snoring, pauses in breathing during sleep, or marked daytime sleepiness, a clinician may evaluate for sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, which can strongly affect attention and memory. Cognitive screening or neuropsychological testing: If memory or thinking problems are prominent, structured assessments can help clarify which domains are affected and guide next steps. Other targeted tests: Depending on the pattern of symptoms, a clinician may advise additional evaluations related to balance, vision, hearing, or autonomic function. In many people, lifestyle factors and common medical contributors are identified through history, examination, and blood tests. Imaging is typically reserved for situations where the symptom pattern suggests a need to rule out neurological disease. Medical Treatment for Brain Fog Because brain fog is a symptom cluster rather than a single diagnosis, medical treatment depends on the underlying cause. The goal is usually to identify and address what is driving the fog, then support recovery with practical measures. A clinician may consider medical treatment approaches such as: Reviewing medications: If brain fog started after a new medicine or a dose change, a doctor may adjust timing, switch to an alternative, or reduce dose when clinically appropriate. Treating thyroid imbalance: If thyroid hormones are outside the healthy range, treatment can improve fatigue, attention, and mental clarity over time. Correcting anaemia or iron deficiency: If testing suggests low iron or anaemia, treatment may include diet changes and iron therapy under medical guidance. Treating vitamin B12 deficiency: B12 deficiency is a treatable cause of fatigue and cognitive symptoms. Treatment may involve oral supplements or injections, depending on the cause and severity. Managing blood sugar issues: If glucose fluctuations or diabetes are contributing, a treatment plan may include dietary adjustments, activity, and medications as advised. Addressing sleep disorders: Conditions like sleep apnea can cause significant daytime fog. Treatment can meaningfully improve attention, mood, and energy. Supporting mental health: If anxiety or depression is contributing, treatment may involve therapy, structured lifestyle changes, and sometimes medication, guided by a clinician. Treating infections or inflammatory causes: If brain fog follows an illness and symptoms persist or worsen, medical evaluation helps rule out complications and guide appropriate treatment. If brain fog is severe, sudden, or paired with neurological symptoms, treatment is urgent and focused on ruling out time-sensitive conditions such as stroke or serious infection. Can Supplements Help With Brain Fog? Supplements can help in specific situations, but they are not a universal fix. In general, supplements are most useful when they correct a confirmed deficiency or support a clinician-guided plan. Situations where supplements may be considered include: Vitamin B12: Particularly relevant for people with low levels, vegetarian or vegan diets, or absorption issues. Iron: Helpful only when iron deficiency is confirmed, since unnecessary iron can be harmful. Vitamin D: Sometimes used when low levels are found during fatigue and wellness evaluation. Omega-3 fats: Often discussed for brain health, though effects on day-to-day fog can vary by person. Practical guidance: Test first when possible, especially for B12, iron, and vitamin D. Avoid stacking multiple supplements at high doses. Tell your clinician about supplements, especially if you take blood thinners, thyroid medicines, diabetes medicines, or anti-seizure medicines. Be cautious with products marketed as “brain boosters” or “nootropics.” Many have limited evidence, and some can worsen sleep, anxiety, or heart rate. If you choose to try a supplement, a simple approach is best: one change at a time, for a defined period, with attention to sleep, hydration, and diet. Can Brain Fog Be Prevented? You cannot prevent every episode, but you can reduce the chances and severity. Maintain consistent sleep Eat regular balanced meals and stay hydrated Manage stress and build recovery time Move daily, even lightly Review medications with your clinician if symptoms start after a new prescription Keep chronic conditions monitored and follow medical advice Frequently Asked Questions What is brain fog meaning in simple words? Brain fog means feeling mentally cloudy, with difficulty focusing, thinking clearly, or remembering things. Is brain fog a disease? No. Brain fog is not a disease. It is a group of symptoms that can have many causes. What are the most common brain fog symptoms? Poor focus, forgetfulness, slow thinking, word-finding difficulty, mental fatigue, and trouble multitasking are common. What causes brain fog in daily life? Poor sleep, stress, dehydration, irregular meals, sugary foods, alcohol, and mental overload are common triggers. Can stress and poor sleep really cause brain fog? Yes. Poor sleep affects attention and memory, and stress increases mental fatigue and reduces clarity. How long does brain fog last? It varies. It can last days or weeks. If it persists beyond 2 to 3 weeks or worsens, speak with a clinician. Brain fog vs dementia: what is the difference? Brain fog often fluctuates and may improve when triggers are addressed. Dementia is generally progressive and affects daily functioning over time. What helps brain fog fast? Hydration, regular meals, improved sleep timing, reducing late caffeine and alcohol, short walks, and screen-free breaks can help within 24 to 72 hours for many people. When should I see a doctor for brain fog? If it lasts more than 2 to 3 weeks, worsens, affects daily tasks or safety, or comes with new symptoms like weakness or persistent headaches. Which blood tests can help find causes of brain fog? Common tests include CBC, thyroid profile, vitamin B12, vitamin D, glucose or HbA1c, electrolytes, and sometimes iron studies and CRP based on symptoms.

Brain MRI: What It Detects, Procedure and Report Terms

A head MRI, also called a brain MRI, is one of the most common scans used to look closely at the brain and nearby structures. People often search for “MRI head” when they have symptoms like headaches that will not settle, dizziness, seizures, changes in vision, memory concerns, or unexplained weakness. The idea of lying inside a scanner can feel intimidating, especially if you have never had imaging before. The good news is that a head MRI is painless and does not use radiation. It uses a strong magnet and radio waves to create detailed pictures of soft tissues, which helps clinicians understand what is happening and what to do next. This guide explains what a head MRI can detect, how to prepare, what happens during the scan, what “contrast” means, and how to make sense of common MRI report terms. Medical note: This article is for general education and does not replace medical advice. Always discuss your results and next steps with your clinician. What Is a Brain MRI? A head MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is a scan that creates detailed images of the brain and surrounding tissues using a powerful magnet, radio waves, and a computer. It is often called a brain MRI, and in day-to-day practice the terms are usually used interchangeably. Unlike X-rays and CT scans, an MRI does not use ionizing radiation. That makes it a preferred option in many situations where detailed soft-tissue imaging is important. What Can a Brain MRI Detect? A head MRI can help clinicians look for changes in the brain’s structure, blood flow patterns, and surrounding tissues. It may be used to detect or assess: Stroke-related changes, including early stroke changes in certain MRI sequences Bleeding, swelling, or fluid build-up Tumours or other masses Inflammation and some infections Conditions that affect the brain’s white matter, including demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis Structural abnormalities, including developmental changes Pituitary gland issues and nearby structures (in dedicated pituitary MRI studies) Causes of seizures, depending on the clinical context Inner ear and eye-related structures (in some protocols), plus cranial nerves A head MRI can also be used to monitor known conditions over time, such as changes after treatment, stability of lesions, or follow-up for ongoing symptoms. When Is a Head MRI Recommended? A clinician may suggest an MRI head scan when symptoms need deeper evaluation, for example: Persistent or unusual headaches, especially with additional symptoms Seizures or unexplained fainting episodes Dizziness or balance problems that are ongoing or severe Sudden changes in vision, hearing, or speech New weakness, numbness, or coordination changes Memory or thinking changes that need further assessment Symptoms after head injury, depending on the situation and timing Hormonal symptoms when pituitary involvement is suspected In emergencies, CT is sometimes used first because it is faster and widely available. MRI is often used next, or when more detail is needed. Head MRI vs CT Scan: What Is the Difference? Both CT and MRI can image the brain, but they do it differently. CT scans use X-rays. They are fast and helpful in many emergency settings. MRI scans use magnets and radio waves. They usually take longer but provide more detailed views of brain soft tissue. Your clinician chooses the test based on symptoms, urgency, and the question they are trying to answer. Head MRI With Contrast: What It Means Some brain MRI exams are done “with contrast.” This means a contrast agent, commonly a gadolinium-based dye, is injected into a vein during the scan to help certain tissues show up more clearly. Contrast can improve the visibility of: Some tumours and patterns of inflammation Certain infections Blood vessels and areas of abnormal blood supply Specific changes after stroke (depending on timing and protocol) Not every MRI needs contrast. Many are done without it, and your clinician or radiology team decides based on your symptoms and the best imaging approach. Important safety note: If you have kidney disease, have had a previous reaction to contrast, or are pregnant or might be pregnant, tell your clinician and the MRI staff before the scan. They can decide what is safest for you. How to Prepare for a Head MRI Preparation is usually simple, but the safety checklist matters. Before You Arrive Follow instructions from the imaging centre, especially if contrast is planned. Some centres may ask you to avoid eating for a few hours beforehand. Take your regular medications unless your clinician advises otherwise. Wear comfortable clothing. You may be asked to change into a gown. Remove Metal and Mention Implants MRI magnets are strong, so you must remove metal items such as: Jewellery, watches, hairpins, and belts Credit cards and phones (they can be damaged) Removable dental items, hearing aids, and some wearable devices Tell the team if you have any implants or metal in your body, such as: Pacemaker or implanted defibrillator Cochlear implant Aneurysm clip Metal fragments from past injuries or work exposures Implanted pumps or stimulators Some types of surgical hardware Many implants are MRI-safe or MRI-conditional, but the team needs details to confirm safety. If You Have Claustrophobia If enclosed spaces make you anxious, you are not alone. Options may include: A mild sedative prescribed in advance A wide-bore or open MRI machine if available Practical tips like closing your eyes, focusing on breathing, or listening to music through headphones If sedation is used, you may need someone to accompany you home. What Happens During the Scan? A head MRI is usually painless, but it requires stillness and patience. Step by Step You lie on a table that slides into the MRI scanner. A “head coil” is positioned around your head, like a helmet frame, to help capture clear images. The scan begins. You will hear loud tapping, knocking, or humming sounds in short sequences. Earplugs or headphones are provided. You must stay very still. Even small movements can blur images. If contrast is needed, an IV is used to inject it during the scan. How Long It Takes Most brain MRI scans take about 30 to 60 minutes, sometimes longer depending on the protocol and whether contrast is used. What You Might Feel No pain from the scan itself The table may feel firm or cool (you can request a blanket in many centres) Some people feel warm in the scanned area If contrast is given, a brief cool sensation in the arm is common, and some people notice a temporary metallic taste After the Scan: What to Expect If you did not receive sedation, you can usually: Eat and drink normally Resume normal activities right away If you received a sedative, you may need: A short recovery period Someone to drive you home Instructions about resting for the remainder of the day A radiologist reviews the images and sends a report to the clinician who ordered the scan. The timeline varies, but many reports are available within a day or two. Common Head MRI Report Terms and What They Usually Mean MRI reports are written for clinicians, so the wording can sound alarming even when findings are minor or expected. Below are common terms and plain-language explanations. These are general explanations, not a diagnosis. “No Acute Intracranial Abnormality” This often means there is no clear evidence of a recent major problem, such as a large bleed, a significant mass, or a major acute stroke pattern on the sequences reviewed. “Incidental Finding” An incidental finding is something seen on the scan that was not the main reason for the MRI. Many incidental findings are harmless, but some require monitoring. “Lesion” A lesion is a general word for an area that looks different from surrounding tissue. It does not automatically mean cancer. Context and pattern matter. “White Matter Changes” or “White Matter Hyperintensities” White matter refers to the brain’s communication pathways. “Changes” can be seen for many reasons, including age-related changes, migraine-associated patterns in some people, vascular risk factors, and inflammatory conditions. The significance depends on your age, symptoms, and health history. “FLAIR Hyperintensity” FLAIR is a type of MRI sequence. A “hyperintensity” means an area appears brighter on that sequence. It is a description, not a diagnosis. “Restricted Diffusion” or “DWI” Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) looks at how water moves in tissue. “Restricted diffusion” can be seen in certain acute processes such as early stroke, but it can also appear in other conditions. It must be interpreted with the full scan and your symptoms. “Enhancement” If contrast is used, “enhancement” means an area takes up contrast and appears brighter. This can occur with inflammation, infection, some tumours, and other processes. The pattern of enhancement is important. “Edema” Edema means swelling, often due to fluid in tissue. MRI can show edema around tumours, after injury, or with inflammation. “Mass Effect” and “Midline Shift” “Mass effect” means something is pressing on nearby structures. “Midline shift” means pressure has moved structures away from the centre line. These terms are taken seriously and usually require urgent clinical correlation. “Atrophy” or “Volume Loss” Atrophy refers to reduced brain volume. Some degree can occur with aging. The report often describes where it is seen and whether it appears more than expected for age. “Ventricles” Ventricles are fluid-filled spaces in the brain. The report may describe them as normal, prominent, enlarged, or compressed, depending on what is seen. “Sinus Mucosal Thickening” This usually refers to inflammation in the sinus lining. It can be related to sinus congestion and is commonly incidental on head imaging. “Artifact” An artifact is image distortion, often from movement, dental work, or metal. It does not mean disease, it means image quality was affected. Tip: If a report worries you, ask your clinician two simple questions: What findings matter for my symptoms? What happens next, if anything? MRI Safety and Risks A head MRI is considered very safe for most people, but there are a few important safety points: The magnet can interact with certain implants or metal fragments, so screening is essential. Contrast reactions are uncommon, and serious allergic reactions are rare. Gadolinium contrast is handled carefully in people with significant kidney disease. Pregnancy considerations vary by trimester and urgency, so always inform your clinician if you are pregnant or might be pregnant. The radiology team’s screening questions may feel repetitive, but they are there to keep you safe. Frequently Asked Questions Is a head MRI the same as a brain MRI? In most cases, yes. Both terms are commonly used for the same scan of the brain and structures in the head. Some protocols focus on specific areas, such as the pituitary gland. Does an MRI head scan use radiation? No. MRI uses magnets and radio waves, not ionizing radiation. How long does a brain MRI take? Commonly 30 to 60 minutes, sometimes longer depending on the protocol and whether contrast is used. What is contrast and do I need it? Contrast is a dye injected through an IV to improve visibility of certain tissues. Not all MRIs need it. The decision depends on symptoms and what the clinician is looking for. What if I have claustrophobia? Many centres offer options such as headphones, mirrors, calming techniques, wide-bore scanners, or sedation when appropriate. Tell the team in advance. Can I eat before a head MRI? Often yes, but instructions can vary, especially if contrast or sedation is planned. Follow the imaging centre’s guidance. When will I get results? A radiologist reviews the scan and sends a report to your clinician. Many reports are available within a day or two, but timelines vary. What should I do if my MRI report has scary terms? Do not panic based on wording alone. Reports use technical descriptions. Discuss what the findings mean in your situation with your clinician.

Brainstem: Functions, Parts, and Common Conditions

Your heartbeat stays steady, your breathing adjusts to what you are doing, you swallow without thinking, you keep your balance while walking, and you stay alert enough to respond to the world. Most of this happens automatically, without you giving a single instruction. A major reason is the brainstem. The brainstem is a small but vital structure that connects the brain to the spinal cord and helps run many core functions that keep you alive and functioning. In this guide, you will learn what the brainstem is, where it sits, its three main parts, what it controls, which symptoms matter, and how doctors check it. Medical note: This content is for education only and is not a substitute for medical advice. What Is The Brainstem? The brainstem is the stalk-like connection between the brain and the spinal cord. It keeps essential functions running automatically and acts as a major signal highway between the brain and the rest of the body. Brainstem in one sentence: The brainstem is the body’s built-in control and relay centre that keeps life-support functions running while carrying messages between the brain and spinal cord. Where Is The Brainstem Located And Why Is It So Important? The brainstem sits at the base of the brain, in front of the cerebellum, and continues downward into the spinal cord. It is small compared with the rest of the brain, but it is packed with critical pathways and control centres. Why it matters is simple: the brainstem helps regulate core survival functions like breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. It also supports alertness, basic reflexes that protect you (like coughing and swallowing), and constant communication between the brain and body. Because so many important functions pass through such a compact area, even small problems in the brainstem can cause noticeable symptoms. Visual idea: A simple labelled diagram showing the cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord, with arrows indicating two-way signal flow. Brain Stem Parts (Anatomy) Explained The brainstem has three main parts: the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. Midbrain (Top Portion) The midbrain sits at the top of the brainstem. It plays a key role in: Eye movement control Visual and hearing reflexes Support for motor control Sleep-wake regulation and attention-related processes If you think of the brainstem as a busy junction, the midbrain is one of the upper control hubs where movement and sensory reflexes meet. Pons (Middle Portion) The pons is the middle section. It helps: Relay signals between the cerebrum and cerebellum Regulate breathing patterns Support sleep and arousal Coordinate facial sensation and movement Support hearing and balance pathways The pons is also a major “bridge” for communication, which is exactly what its name suggests. Medulla Oblongata (Lowest Portion) The medulla oblongata is the lowest part of the brainstem and merges into the spinal cord. It helps regulate: Breathing Heart rate Blood pressure Swallowing Coughing and vomiting reflexes Because these functions are so fundamental, the medulla is often described as one of the most essential control centres in the nervous system. Think of the brainstem as a connector plus an autopilot: it connects the brain to the body while automatically running vital functions you should not have to think about. Brain Stem Function (What It Controls) The brainstem’s job can be understood in four simple buckets: life support, alertness, relay, and reflexes. Life Support Functions You Do Not Think About The brainstem helps regulate functions that run continuously: Breathing rhythm and airway protection: It supports the breathing pattern and protective actions like coughing if something “goes down the wrong way.” Heart rate and blood pressure regulation: It helps keep circulation stable, especially as you rest, stand, exercise, or feel stress. Basic autonomic balance support: It contributes to the automatic side of the nervous system that keeps internal systems steady. These are not “on or off” switches. They are constant adjustments, minute by minute, that keep your body in balance. Alertness, Consciousness, And Sleep-Wake Control A network within the brainstem called the reticular formation helps regulate wakefulness, attention, and the sleep-wake cycle. In plain language, it is one of the systems that helps your brain stay “online” enough to be aware of your surroundings and to shift between being alert and being asleep. When this system is affected, people may feel unusually drowsy, less responsive, or mentally slowed, depending on the cause and severity. The Brain’s Main Relay Station The brainstem is a two-way highway: It sends motor commands down from the brain to the body. It brings sensory information up from the body to the brain. Messages travel through the brainstem all day, every day, whether you are moving, speaking, swallowing, or just maintaining posture and balance. Brainstem Reflexes That Protect You Many protective reflexes are coordinated through the brainstem, including: Pupillary light reflex: pupils adjust to bright or dim light Swallow and gag reflex: helps protect the airway and move food safely Cough and sneeze reflexes: help clear irritants Eye stabilization during head movement (vestibulo-ocular reflex): helps keep vision steady when you move These reflexes are fast and automatic, and they exist to protect you and keep basic functions stable. Brainstem And Cranial Nerves (What The Brainstem Helps You Do) Cranial nerves are like specialized “wires” that control and carry information for the face, eyes, hearing, balance, swallowing, voice, and more. Many of the control centres for these nerves sit in or connect through the brainstem, which is why brainstem health is closely tied to things like eye movement, facial strength, speech clarity, and swallowing. Quick Map By Region Midbrain: Key control for eye movements and visual reflexes Pons: Facial movement and sensation, hearing and balance support Medulla: Swallowing and voice support, heart and breathing regulation support Here is a simple way to connect function to everyday experience: Function Area What It Helps With What Someone Might Notice If Affected Eye movement control Coordinated gaze, steady vision Double vision, trouble tracking, unusual eye movement symptoms Facial sensation and movement Facial expressions, sensation Facial numbness, drooping, changes in expression Swallowing and voice Safe swallowing, clear speech Choking, coughing while eating, hoarse voice, slurred speech Balance pathways Stable posture and coordination Dizziness, vertigo, unsteady walking Symptoms can overlap with many other conditions, so this table is not for self-diagnosis. It is simply a way to understand why the brainstem can affect multiple functions at once. Common Conditions That Can Affect The Brainstem Many different issues can involve the brainstem. Most people never have a brainstem condition, but it helps to understand the broad categories. Vascular events: Reduced blood flow or bleeding can affect brainstem function. Head injury and trauma: Impact injuries can affect brain tissue directly or through swelling. Infections and inflammation: Some infections can involve the brain or the tissues around it, leading to brainstem-related symptoms. Growths or pressure effects: Masses, swelling, or fluid-related pressure can crowd nearby structures. Demyelinating or nerve-signal conditions: Some conditions disrupt how nerve signals travel. Structural or congenital issues: Certain structural patterns can crowd the lower part of the brain, sometimes affecting brainstem and nearby pathways. Metabolic issues: Severe imbalances, such as significant electrolyte disturbances, can affect brain function and alertness. A key point: symptoms vary widely because many pathways pass through a small space. The same symptom, like dizziness or slurred speech, can also come from causes outside the brainstem. That is why clinical evaluation matters. Signs And Symptoms Linked To Brainstem Involvement Symptoms People Commonly Notice People may notice one or more of these symptoms when brainstem pathways are involved: Dizziness or vertigo Double vision or unusual eye movement symptoms Slurred speech Swallowing difficulty Balance and coordination problems Weakness or numbness Changes in alertness or unusual sleepiness These symptoms can have many explanations, including non-brainstem causes. What matters most is the pattern, severity, and timing. Red Flags That Need Urgent Medical Care Seek urgent medical care if you or someone else has: Sudden one-sided weakness or numbness Facial drooping Trouble speaking or understanding speech Sudden severe headache Fainting, severe confusion, or reduced consciousness New seizure Sudden vision loss Severe imbalance that starts suddenly Breathing difficulty or repeated choking If symptoms begin suddenly or worsen quickly, do not wait it out. Sudden neurological symptoms should be treated as time-sensitive. How Doctors Check The Brainstem History And Basic Examination A clinician usually starts with a careful history and exam. This often includes: Symptom timing (sudden vs gradual) Triggers and what makes symptoms better or worse Current medications and recent medication changes Recent illness or injury Relevant medical history such as blood pressure, blood sugar issues, or prior neurological concerns A focused neurological exam may include checks of: Eye movements and pupil response Facial movements Speech clarity Swallowing and voice quality Coordination and balance Strength and sensation Reflexes This exam helps narrow down which pathways might be involved and what testing is most useful. Imaging Tests (When Clinically Advised) Imaging is not always needed, but it can be crucial depending on symptoms. MRI: A detailed soft-tissue scan that can evaluate brain structures closely, including the brainstem. It is often used when doctors need high-detail information. CT: A faster scan often used in emergencies, especially when speed matters. The choice depends on the situation, symptoms, and what the clinician is trying to rule out. Other Tests That May Help In Specific Cases Depending on symptoms and clinical judgement, a doctor may consider: Hearing and balance related testing: when dizziness, vertigo, or hearing changes are prominent Evoked potential testing: when a clinician wants information about how certain nerve pathways are conducting signals Swallow evaluation: when choking, coughing during meals, or swallowing difficulty is present Blood Tests That May Help Identify Contributing Factors Your clinician may recommend tests to rule out common contributors, especially when symptoms like dizziness, fatigue, or mental fog overlap with broader health issues: Complete Blood Count (CBC) Electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium) Blood glucose or HbA1c Thyroid profile (TSH, T3, T4) Vitamin B12 Inflammation marker such as CRP (when relevant) If your clinician recommends lab tests, you can book them with Metropolis Healthcare and review the results with your doctor to understand what they mean in your specific context. Brainstem Health Basics You cannot “exercise” the brainstem directly, but you can reduce risks and support overall nervous system health: Wear helmets and seatbelts, and prevent falls: many serious neurological injuries are preventable. Manage blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol if advised: vascular health supports brain health. Support sleep and stress recovery: steady sleep and stress management support attention, balance, and overall nervous system function. Medication safety matters: do not stop or change medicines without medical guidance. If symptoms started after a new medication, tell your clinician. When symptoms change suddenly, do not wait: sudden neurological symptoms should be assessed urgently. FAQs What Is The Brainstem And What Does It Do? The brainstem connects the brain to the spinal cord. It helps regulate essential automatic functions like breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, alertness, and protective reflexes, while also carrying messages between the brain and body. What Are The Three Parts Of The Brainstem? The brainstem has three main parts: the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. What Is The Function Of The Medulla Oblongata? The medulla supports vital functions such as breathing, heart rate, blood pressure regulation, and protective reflexes like swallowing and coughing. It also merges into the spinal cord. How Does The Brainstem Control Breathing And Heart Rate? The brainstem contains control centres that continuously adjust breathing rhythm and heart activity based on the body’s needs, such as rest, movement, and stress. Which Cranial Nerves Are Connected To The Brainstem? Many cranial nerve control centres sit in the brainstem. These nerves are involved in eye movements, facial sensation and movement, hearing and balance, swallowing, and voice. What Are Common Brainstem Reflexes? Common brainstem reflexes include pupil response to light, swallowing and gag reflexes, coughing and sneezing reflexes, and eye stabilization when the head moves. What Symptoms Could Suggest A Brainstem Problem? Possible symptoms include dizziness or vertigo, double vision, slurred speech, swallowing difficulty, imbalance, weakness or numbness, and unusual sleepiness. These symptoms can also come from other causes, so medical evaluation is important. Can A Brainstem Injury Be Treated Or Improved? Treatment depends on the cause. Some brainstem problems improve with prompt care, rehabilitation, and targeted treatment, while others require urgent intervention. Early assessment often improves outcomes. Why Is MRI Used To Look At The Brainstem? MRI provides detailed images of soft tissues and can help evaluate brain structures closely, including the brainstem. Doctors choose MRI or CT based on urgency, symptoms, and clinical goals. What Is The Difference Between Coma, Brain Death, And Brainstem Function Loss? Coma refers to a state of unresponsiveness where a person is not awake and not aware. Brain death is an irreversible loss of brain function, which includes loss of brainstem function. Brainstem function loss is particularly critical because the brainstem supports breathing and other life-sustaining reflexes. These are complex medical determinations made by trained clinicians using established protocols.

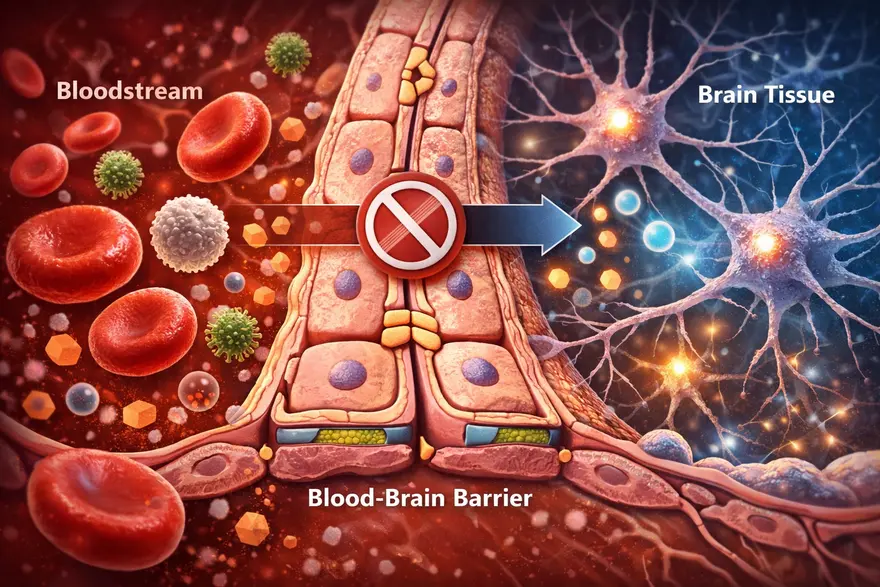

Blood-Brain Barrier: What It Is And Why It Matters